|

I’m all about helping composers "up" their composing for singers game—everything from text setting to poetry permissions to range, tessitura, and voice types & more!

It’s a particularly important subject during this current renaissance of new opera. So many composers are developing new operatic works. But there’s someone else to keep in mind as you write your vocal works. Someone who often gets overlooked, ESPECIALLY in opera writing. Your pianist. If you’re writing an opera, you’ve probably heard about taking your orchestral or chamber score and creating a piano reduction—a rehearsal score that singers will use in lessons, coachings, musical, and staging rehearsals. These rehearsals are ALL done with only a rehearsal pianist—not the full ensemble—for budget reasons. The instrumental ensemble only joins for the very last few rehearsals. My #1 tip for you: Make sure that piano part is beautiful, idiomatic, and artistic. Make sure that it stands ON ITS OWN. Why?

The sad fact is that many of the piano reductions I see are simply NOT playable. They suspiciously like what notation software spits out when you use their automatic “arrange” functions. This forces your pianist to rework your reduction in real time during practice and rehearsal, crossing out notes that don’t fit in their hands, leaps that are impractical, and sometimes even cutting out that chord or motive that is supposed to be an important cue for the singers—YIKES! Don’t let that be you. Take that extra time (and negotiate for extra money in your commissioning fee!) to make sure that the piano reduction isn’t just an automated “arrangement” of what the ensemble plays, but a thoughtfully composed piano version. A version that provides all the necessary elements for the director, designer, and singers to rehearse and stage your show AND that makes expressive, beautiful, crafted music on its own. It’s more work. But it’s worth it. How much do you charge for your music?

That question can make composers sweat bullets! Maybe this is you...

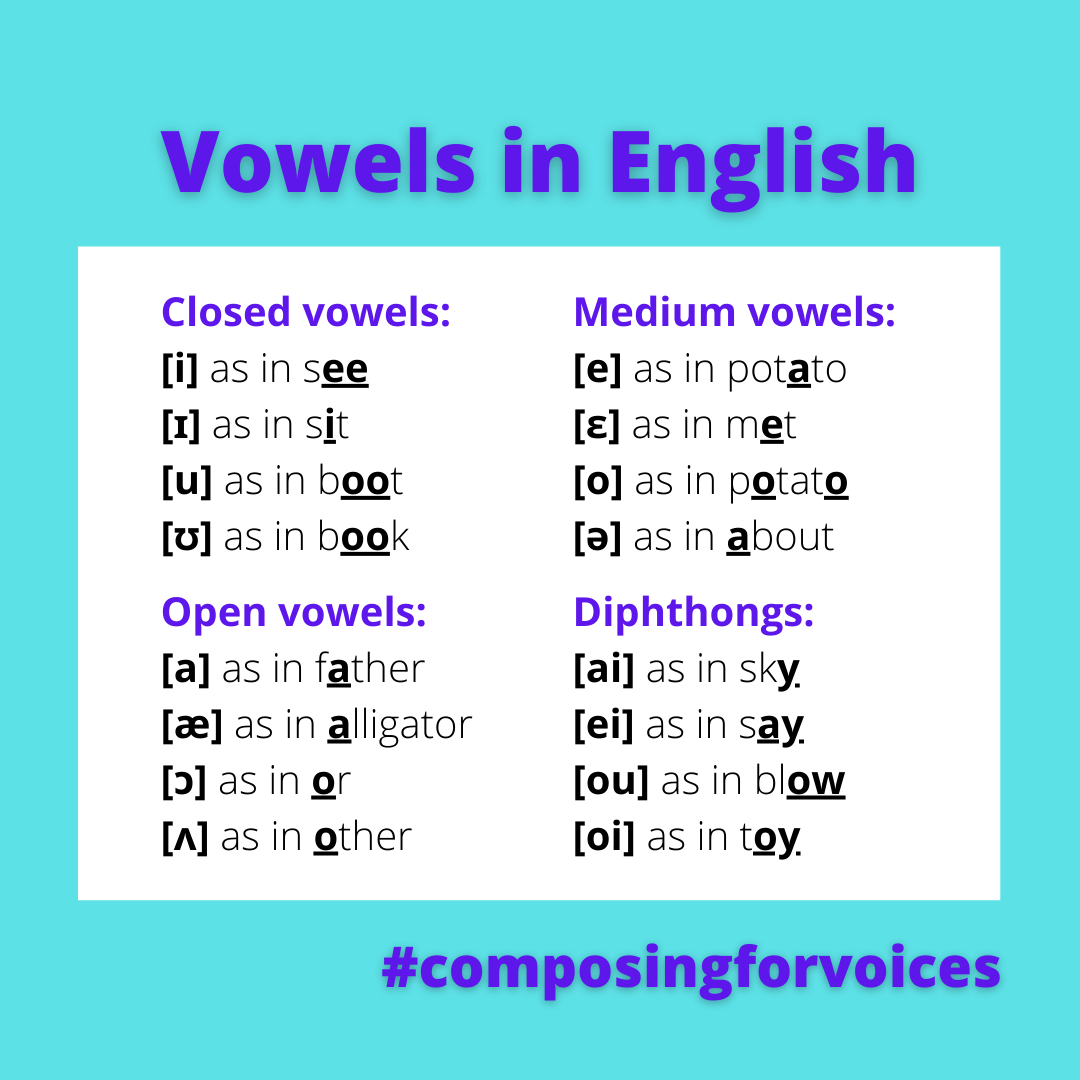

When that moment happens, you need to be ready. Because pretty soon, the conversation is going to move from what kind of piece they want and what they love about your music to the scariest of questions: "How much do you charge?" The most important step you need to take? Figure out your rates now. Here are a few resources you can consult: New Music Box Commissioning Fees Calculator Canadian League of Composers Commissioning Rates New Music USA's Commissioning Music: A Basic Guide Meet the Composer's Guide to Commissioning Music Dominick DiOrio's Guide to Commissioning Music (especially helpful for choral works) American Composers Forum Commissioning By Individuals Guide Have a look through these tools and documents. As you read, notice: how do these rates make you feel? Excited? Nervous? Affirmed? Terrified? Do you feel ready to ask a commissioner to pay you these rates? Why nor why not? Drop me a line and let me know. Listen to any art song, opera aria, choral work, or your favorite pop song, and you'll find something in common: dramatic high notes. Those awesome moments in a piece of music that create drama and intensity by singing in the upper register. The trouble is, sometimes, they're written in a way that causes this effort to create a real MOMENT fall FLAT. Let me explain. To sing a high note, a singer's mouth needs to be open tall in order to get the best sound and have the best chance of singing it with ease. And because singers perform text, it makes a HUGE difference what word you've chosen to set for that dramatic moment. That's because words are combinations of vowels and consonants, and because singers sustain vowels for most of the length of any given pitch. 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘷𝘰𝘸𝘦𝘭𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘦𝘲𝘶𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘴𝘶𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘩𝘪𝘨𝘩 𝘱𝘪𝘵𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘴. Here's why: vowels can be open, medium, or closed. Try this: Speak the words on the vowel chart slowly while watching your mouth in a mirror. Pay attention to what you see and feel. Notice that closed vowels involve closure of the mouth space either through lip rounding (boot, book) or through activation of the tongue into a little arch (see, sit). For the medium vowels, the lips are a little less rounded (potato) and the tongue is less arched (potato, met) or fairly neutral (about). And for the open vowels, lip rounding is even less (or), and the tongue is pretty much at rest in the bottom of the jaw (alligator, father, other). See why they’re called open vowels? There’s literally less going on in the mouth and around the lips! Now that you’ve tried this out, let me give you a handy principle to keep in mind: A property of singing is that high notes require a taller mouth than low ones. As singers ascend in range, we drop our jaws and lift the yawn space (soft palate) behind our upper molars to create more vertical space. And that’s why the open vowels can be sung on high notes more easily & beautifully while also being better understood by the audience! Let's take this a littler further. Diphthongs are single syllables that combine two vowel sounds (di = two, phthong = sound). They are super common in English. Try this: Slowly speak the diphthongs and identify which components are open, medium, and closed. Which diphthongs will be more successful on a high note? Let me know in the comments! My friend Danielle Kuntz, harpist asked a great question on Twitter today: How do we support and encourage living composers? I love this question, and it's one I get a lot. Performers, ensemble directors, music teachers, and music fans know that the odds have been stacked against living composers for a while. They want to take meaningful action, and they also know they can't do it all at once or all on their own. Many performers I talk to get stuck because they want to offer composers big commissions but don't have a dedicated funding source for that. It doesn't have to be hard to support living composers. You can get started right now. It doesn't have to cost a thing. Here's a list of 21 ways you can support living composers:

What did I miss? Get in touch and let me know YOUR favorite ways are to support living composers. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed